England, December 1843

The Spirit of Christmas Immediately Past

A Christmas Carol was written when English Christmas traditions had been in a centuries-old decline. Most of the holiday traditions Dickens recounts in A Christmas Carol have roots in the Roman Saturnalia and the Saxon holiday of Yule and are much older than Christianity. In fact, in many periods throughout history of Christianity, these traditions were even “sinful.”

For most of their history, the English lived in rural areas and rarely left the place where they grew up. “Christmas” was a twelve-day festival taking place in the manor of the local “lord,” and included the burning of the Yule log, playing traditional games, and feasting on traditional foods.

In the mid-seventeenth century, the Comwellian Revolt abolished Christmas as well as the monarchy. However well the monarchy was subsequently “restored,” the traditions of the winter holiday never recovered. But religious prescription was not the only cause of the decline of Christmas. Even by the beginning of the nineteenth-century, the industrial revolution, especially in the north, was changing the communities that still tenuously kept the customs of their ancestors.

In the mid-seventeenth century, the Comwellian Revolt abolished Christmas as well as the monarchy. However well the monarchy was subsequently “restored,” the traditions of the winter holiday never recovered. But religious prescription was not the only cause of the decline of Christmas. Even by the beginning of the nineteenth-century, the industrial revolution, especially in the north, was changing the communities that still tenuously kept the customs of their ancestors.

By the time the Carol was written in 1843, the lavish celebrations of the past were a distant, quaint memory. Some still remembered them, and then even begore the Carol a few popular books attempted to record the celebrations of the past, such as The Book of Christmas by T.H. Hervey (1837) and The Keeping of Christmas at Bracebridge Hall by Washington Irving (1820). But social forces beyond simple nostalgia were at work, rekindling the need for winter celebrations.

Better employment prospects in the cities prompted many people to leave their homes for jobs in the cities. More and more boys were being sent away to school, and their winter homecoming inspired celebrations that drew upon what traditions could be remembered.

Dickens was one of the first to show his readers a new way of celebrating the old holiday in their modern lives. His Christmas celebrations of the Carol adapted the twelve-day manorial feast to a one-day party any family could hold in their own urban home. Instead of gathering together an entire village, Dickens showed his readers the celebration of Fred, Scrooge’s nephew, with his immediate family and close friends, and also the Cratchits’ “nuclear family”: perfectly happy alone, without the presence of friends or wider family. He showed the urban, industrial English that they could still celebrate Christmas, even though the old manorial twelve-day celebrations were out of their reach. Dickens’s version of the holiday evoked the childhood memories of people who had moved to cities as adults.

A Christmas Carol without Christ

The Carol was first published in a time of great religious controversy, and its lack of babes, wisemen, stars, mangers, and other icons of the Christian nativity inspired a multitude of sermons and pamphlets. Some religious leaders believed that any story of Christmas without references to the birth of Jesus were self-indulgent and unchristian, and that the ritualistic celebrations in the story were pagan and sinful.

Although A Christmas Carol is generally associated with the Christian winter holiday season, for it does contain references to the Christian Jesus; its themes are not exclusive to Christianity and it inspired a tradition for decades in Christmas books and celebrations that appealed to many non-Christians.

Victorian Family Values

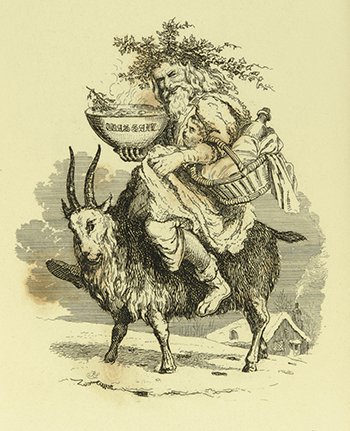

Illustration from The Book of Christmas, by T. H. Hervey, 1837, with which Dickens was probably familiar.

The first readers of A Christmas Carol were able to see themselves in the people shown to Scrooge by the Spirit of Christmas Present. Whiel today the most remembered character of the story is Scrooge, Dickens’s first readers identifies most strongly with the Cratchit family.

The Cratchit family, although quaint and sentimental to modern readers, was a familiar portrait of the lower-middle class families who read the Carol, familiar in fact to Dickens himself, who modeled the Cratchits’ lifestyle on his own childhood experience. Dickens demonstrates that even in poverty, the winter holiday can inspire good will and generosity toward one’s neighbors. He shows that the spirit of Christmas was not lost in the race to industrialize, but can live on in our modern world.

Great debates over the plight of the poor and other social issues were beginning to be the focus of much political discussion during the 1840s. When the Spirit of Christmas Present warns of impending doom for “Man’s Children,” the symbolic “Want and Ignorance,” Dickens’s readers could instantly identify these symbols. They were the offspring of a new industrial society, who filled the new industrial cities.

“Who can listen to the objections regarding such a book as this? It seems to me a national benefit, and to every man or woman who reads it a personal kindness. The last two people I heard speak of it were women; neither know the other, or the author, but both said, by way of criticism, ‘God bless him.’”

William Makepeace Thackerey, 1844

“Though no one claimed in 1843 that Dickens invented Christmas–that hyperbolic suggestion would surface later on–many seemed to feel he had rediscovered it and freed it from puritan constraints.”

Paul Davis, The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge, 1990

“The tale has prompted more positive acts of beneficence…. than can be traced to all the pulpits and confessionals in Christendom, since Christmas 1842.”

Lord Jeffrey, in a letter to Dickens a week after publication of the Carol, 1843

“All persons say how differently this season was observed in their fathers’ days, and speak of old ceremonies and old festivities as things which are obsolete. The cause is obvious. In large towns the population is continually shifting; a new settler neither continues the customs of his own province in a place where they would be strange, nor adopts those which he finds, because they are strange to him, and thus all local differences are wearing out.”

Robert Southey, 1807

“There is no doubt that, by reason of his little Christmas Books, Dickens had distinctly identified himself with the festive season, to which he thus imparted a touch of joviality and good-feeling of the old-fashioned English kind, so much so that the omission of a Yule-tide story, around which his pen could weave such delightful fancies, was regarded as a real public loss.”

Frederic G. Kitton, 1890