Adaptations

“So the figure itself fluctuated in its distinctness”

Adaptations of A Christmas Carol fall into three rough categories. The first of these is a straight adaptation, or interpretation of the story of the sake of the story, with an attempt to keep as close to the Dickens text as is possible. The second is the use of the story as a medium through which to make an often unrelated point. A Christmas Carol has often been adapted in this manner to political commentary or satire. The third is an exploitation of the story’s popularity or cultural importance as a sure way to make money.

Adaptations of A Christmas Carol fall into three rough categories. The first of these is a straight adaptation, or interpretation of the story of the sake of the story, with an attempt to keep as close to the Dickens text as is possible. The second is the use of the story as a medium through which to make an often unrelated point. A Christmas Carol has often been adapted in this manner to political commentary or satire. The third is an exploitation of the story’s popularity or cultural importance as a sure way to make money.

Even faithful adaptions vary slightly because they contain the opinions and priorities of the writers. J. Edward Parrott explained the changes in his adaptation of A Christmas Carol by explaining that, because he recommended the play for young people, certain scenes were “too tragical in their intensity, and too harrowing in their unpalliating realism.”

Cyclical political and moral attitudes also affect adaptations. In most of the adaptations that stray from Dickens’s original text, many of the changes are representative of the era in which that adaptation was done. For example, before the stock market crash of 1929, an adaptation called An American Carol was a business-based celebration of capitalism. A forward-looking 1928 stage version of A Christmas Carol called Mr. Scrooge contained a “critique of capitalism” and portrayed a Cratchit with “the beginnings of a revolutionary consciousness.”

The older the story gets the looser the interpretations become. Many of late twentieth-century adaptations are based on either the events or the characters in A Christmas Carol, rather than on the story as a whole. For example, Dr. Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas echoes the hard-hearted miser who learns to love the Christmas season. The Frank Capra film, It’s A Wonderful Life depicts the personal transformation following a man’s observations of his life as if he were absent from it.

The adaptations mentioned so far all have a Christmas setting. There have also been similar adaptations for other holidays. A recent Roseanne episode showed Roseanne losing her Halloween spirit, being visited by ghosts of Halloween past, present, and future, and then regaining her love of Halloween pranks. There has also been a version of the Grinch’s story, adapted to Halloween.

Like folklore, perceptions of A Christmas Carol have changed as the story is passed down from one generation to another. Most people are familiar with Dickens’s Carol have never read the original book. Though A Christmas Carol is a literary work written long after the time of oral storytelling had passed, its history is very much that of a folk tale. Anyone who studies the Carol soon sees that the story changes as its audience changes, and it will continue to change in Christmases yet to come.

Dickens’s Own Adaptations

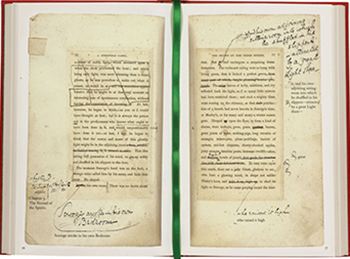

A page of Dickens's own prompt copy of A Christmas Carol

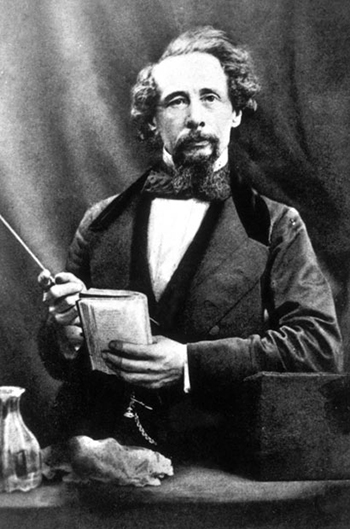

From 1857 until the end of his life, Charles Dickens performed public readings of his books. A Christmas Carol was his most popular and favorite reading. It was the first piece he performed, and the last before his death. Dickens adapted the Carol for performance, shortened it first to three hours, then eventually to an hour and an half. Dickens seldom referred to the prompt copy of A Christmas Carol that he carried onto the stage with him, and each reading was a little different, because he added to and changed the Carol when he read. “I got things out of the old Carol–effects I mean–so entirely new and strong that I quite amazed myself and wondered where I was going next,” he wrote to a friend. The Manchester Examiner in 1867 said of his readings, “There is always a freshness about what Mr. Dickens does–one reading is never anything like a mechanical following of a previous reading, even of the same work.” Another newspaper of the time wrote, “He gave to every character a different voice, a different style, a different face.”

Dickens enjoyed performing because he loved his “public.” Writing of his first audiences at a reading of the Carol, he said, “They lost nothing, misinterpreted nothing, followed everything closely, laughed and cried… and animated me to that extent that I felt we were all bodily going up into the clouds together.”

In 1867 and 1868, Dickens performed in the United States. His readings were so popular that people camped overnight in the streets to buy tickets at box offices, or found tickets sold by scalpers. In Washington, D.C., President Andrew Jackson had tickets for his family every night. The tour was incredibly lucrative. Dickens made $140,000 on the tour, and immense sum for the time. He refused to pay taxes on the income–in protest to a government which for decades had not taken up his cause of international copyright–and was physically protected by the New York City police from the federal tax collectors who came to arrest him the day he boarded ship to return to London.

Adaptations of A Christmas Carol

The following is only a selection of the hundreds of versions, parodies, and adaptations of A Christmas Carol. In many cases the adaptation listed is the first work created in that medium. For example, the first sound recording was in 1905, there have been many after.

| 1844 | A Christmas Carol; or Past, Present and Future. Dramatic adaptation |

| 1850 | Christmas Shadows. A Tale of the Times. Story derivative |

| 1867 | A Christmas Carol. As Condensed by Dickens for his readings |

| 1878 | The Miser. Pantomime |

| 1885 | A Christmas Carol. Being a few scattered staves from a familiar composition, rearranged for performance by a distinguished musical amateur, during the Holiday Season, at H-rw-rd-n. |

| 1893 | “The Spirit of Christmas Present (Passages from a political ‘Christmas Carol’ of the period descriptive of a slumbering Statesman’s Yuletide Dream.)” Political adaptation |

| 1896 | Jobkin’s Christmas Eve. Illustrated parody |

| 1901 | Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost. Silent film |

| 1905 | “The Awakening of Scrooge.” Sound recording |

| 1910 | A Christmas Carol. Silent film by Thomas A. Edison |

| 1912 | “Bob Cratchit’s Speech: Supposed to be Delivered After the Events Depicted in A Christmas Carol.” U.S. newspaper story |

| 1921 | A Christmas Carol. Suite for piano in two parts |

| 1922 | “An Epilogue to A Christmas Carol: Stave VI, The Last of the Four Spirits” |

| 1928 | Mr. Scrooge. A dramatic fantasy with some of the original illustrations by John Lynch [sic] |

| 1928 | Scrooge. Black and white sound film |

| 1928 | A Christmas Carol: The Story of a Sale. With marginal notes for salesmen. Edition which used events in the Carol to teach principles of salesmanship |

| 1930 | A Christmas Carol. Marionette play |

| 1934 | First performance of Lionel Barrymore’s radio production |

| 1946 | A Christmas Carol. Television play |

| 1947 | Men of Goodwill: Variations on “A Christmas Carol” for Orchestra |

| 1955 | A Christmas Carol. Operetta in Two Acts |

| 1956 | The Stingiest Man in Town. TV Musical |

| 1962 | Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol. Animated film |

| 1967 | A Christmas Carol. Television parody. Tom Smothers as Scrooge, Jack Benny as Marley |

| 1970 | Scrooge. Color musical film |

| 1975 | The Passions of Carol. Pornographic film |

| 1978 | A Christmas Carol. Classics Comics (Marvel Comics Group) |

| 1979 | A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by puppets |

| 1983 | Mickey’s Christmas Carol. Disney animated film |

| 1983 | “A Reggae Christmas Carol” in The National Lampoon |

| 1985 | God Bless Us Every One! Being an Imagined Sequel to A Christmas Carol |

| 1986 | John Grin’s Christmas. African-American adaptation by Robert Guillaume |

| 1986 | “It’s a Wonderful Job” Television parody on Moonlighting |

| 1988 | Scrooged. Feature film |

| 1990 | From The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge, by Paul Davis |

Satirical Adaptations

Possibly because of its strong moral message, A Christmas Carol has been used in satire almost since first publication, notably by Punch.

By 1901 Punch’s editors were well aware that readers were amused by pieces ridiculing what had become know as the “Dickens Christmas.”

The Old Style

The Old Style

Nothing could have been more cheerful than the well lighted streets. The holly and the mistletoe glistening in the green-grocers’ windows. Toys were everywhere, and scores of happy children toddled beside their rosy-cheeked parents full of the glee of the joyful season, and so on, and so on, for a dozen pages.

The family party assembled together in the old ancestral hall was a right merry one. The armour reflected back the red glare of the blazing Yule log. Dancing and flirtation and all the brightest side of life were in evidence on all sides. What could have been more delightful? What could have been more in keeping with the good traditions? And so on, and so on, for another dozen pages.

“Ah,” said the host, as he bid adieu to the last guest for the last time smiling, “what a pity it is that Christmas comes but once a year!”

The New Style

Nothing could have been more dismal than the fog-hidden streets. The green–if there were any–could not ben seen in the fruiterer’s windows. The customary cheap presents in the toy shops were hidden by the prevailing gloom. Children by the scores shivered and whimpered as they listened to the querulous voices of their parents. And so on, and so on, for a dozen pages.

The family party assembled in the large dining room quarreled with the utmost heartiness. They had been so intent upon their bickerings that they had quite forgotten to keep up the fire. The coals were as cold as the biting frost without. The hall table was covered with unpaid bills. County Court summonses had been left early in the afternoon and were well in evidence. What could have been more in keeping with the sadness of the dismal season? What could have been more wretched? What could have been more in keeping with the bad traditions? And so on, and so on, for another dozen pages.

“Ah,” said the host, as he bid adieu to the last guest for the first time, smiling, “how fortunate it is that Christmas comes but once a year!”

Long before Murphy Brown vs. Dan Quayle, literary characters have been adapted to illustrate political opinions. Here are three twentieth-century examples, and a Victorian cartoon.

Scrooge as Adapted by Ed Meese

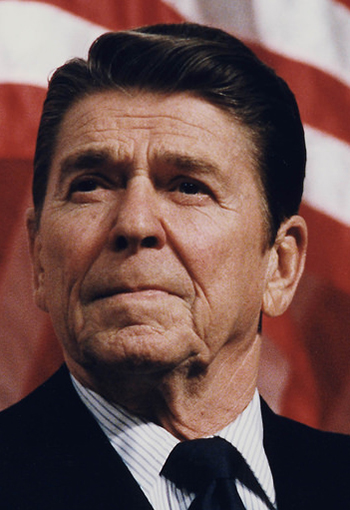

In 1983 Edwin Meese, counselor to President Regan, defended Ebenezer Scrooge, after Regan had been compared to the fictional miser.

In 1983 Edwin Meese, counselor to President Regan, defended Ebenezer Scrooge, after Regan had been compared to the fictional miser.

“Let me say that because it’s the Christmas season, some historical research has revealed a great injustice that I would like to right at this time. As a matter of fact, I found that actually Scrooge had pad press in his time. If you really look at the facts, he didn’t exploit Bob Cratchit. As a matter of fact, Bob Cratchit was paid 10 shillings a week, which was a very good wage at that time.

“Furthermore, the free market wouldn’t allow Scrooge to exploit poor Bob. England didn’t allow free public schools until after Dickens was dead. So that the fact that Bob Cratchit could read and write made him a very valuable clerk and ad a result of that he was paid 10 shillings a week. Bob, in fact, had a good cause to be happy with his situation. He lived in a house, not a tenement. His wife didn’t have to work and only one of his children had not had much of an education, but he still had a job. He was able to afford the traditional Christmas dinner of roast goose and plum pudding. So after all folks, I think we have to change our views. So let’s be fair to Scrooge. He had his faults, but he wasn’t unfair to anyone.”

(As reported in the New York Times, December 15, 1983)

A Christmas Carol as told by “Uncle Ronald”

by Richard Lingeman in The Nation, December 1985

“All right, children, is everybody settled? Good. Stay quiet now, and Uncle Ronald will tell you A Christams Carol by Charles Dickens. Once upon a time, in the city of London, England, there was an honest, hardworking businessman named Ebenezer Scrooge. With his partner, Jacob Marley, Scrooge founded a small but profitable blacking company in Cheapside. Then Marley died and Scrooge was left to run the business alone, assisted by his clerk, a man named Bob Cratchit. This Cratchit fellow wasn’t much help. He was lazy, worthless agitator type who was always trying to organize the other workers into a union. He kept Cratchit on purely out of the goodness of his heart, because Cratchit had a crippled son named Tiny Tim. far from showing his gratitude, however, Cratchit accused his employer of violating child labor laws and threatened to take him to court. Even though Scrooge patiently explained that nobody else would hire 8-year-old children, Cratchit just sneered ‘Bah, Humbug!’

“All right, children, is everybody settled? Good. Stay quiet now, and Uncle Ronald will tell you A Christams Carol by Charles Dickens. Once upon a time, in the city of London, England, there was an honest, hardworking businessman named Ebenezer Scrooge. With his partner, Jacob Marley, Scrooge founded a small but profitable blacking company in Cheapside. Then Marley died and Scrooge was left to run the business alone, assisted by his clerk, a man named Bob Cratchit. This Cratchit fellow wasn’t much help. He was lazy, worthless agitator type who was always trying to organize the other workers into a union. He kept Cratchit on purely out of the goodness of his heart, because Cratchit had a crippled son named Tiny Tim. far from showing his gratitude, however, Cratchit accused his employer of violating child labor laws and threatened to take him to court. Even though Scrooge patiently explained that nobody else would hire 8-year-old children, Cratchit just sneered ‘Bah, Humbug!’

“This Cratchit had no team spirit whatsoever; he was always trying to shirk his duties and constantly nagged Scrooge for days off. Reminds me of certain Federal employees who are too lazy to work on Martin Luther King’s birthday. Nowadays, of course, Cratchit would have been calling for federal boondoggles like the Legal Service Corporation and Aid to Families with Dependent Children and for cuts in defense spending to pay for them.

“Now, where was I? Oh, yes, the straw that broke the camel’s back was Cratchit’s refusal to work on Christmas Day, even though Scrooge was swamped by end-of-the-year inventory. I should think that it would have been the essence of the Christmas spirit for him to help poor Scrooge keep his hours down. But no. Cratchit said he’d promised Tiny Tim he’d be home for Christmas dinner, and if he didn’t come home the boy’s heart would be broken. Now, Scrooge had seen this Tiny Tim and he suspected he was faking a gimpy leg so he could collect disability payments, or whatever they called it in those days. Like father, like son. Cratchit was what was known as an ‘almshouse chiseler,’ which means he was always getting money from poorhouses under the problem of socialism that was prevalent in England before Mrs. Thatcher turned the country around. At any rate, when Cratchit refused to work on Christmas Day, Scrooge just blew his top and fired him.

“Well. Cratchit stormed out, vowing to get revenge. Using money he’d cadged from the almshouse, he went to a pub and had some drinks with an out-of-work actor he knew. This fellow used to play ghosts in Shakespearean plays until he was kicked out of the Stage Actors Guild for un-British activities. The two of them hatched a plot whereby the actor would dress up like a ghost, sneak into Scrooge’s room at midnight and frighten the old man out of his wits.

John Tennial, an illustrator best known for his collaboration with Lewis Carroll, contributed this political satire to Punch, December 1893.

“I’m afraid this bit of blackmail worked all too well, because poor Scrooge had a cardiac condition and was under doctor’s orders not to get excited. The ghost told him in a deep scary voice to bring a turkey and two bottles of gin to the Cratchit place on Christmas Day or someone would tell the police that he’d been dumping blacking into the Thames and polluting the royal swans. So the next morning he sent the Cratchits a basketful of food, and they all got high on plum pudding. Cratchit was so elated by his success that he persuaded his co-workers to go on strike, and Scrooge finally had to move his blacking business to India.

“So that’s my story, children. Happy holidays to you all, and by golly, even if it is illegal to teach young people about the Man Upstairs, I’m going to say it: God bless us, every one!”

“[The Spirit of Christmas Present] will show Scrooge the most horrible sight of all–Scrooge. And having shown, smash him and his power for evil once for all. Rebuild the world.

Already they are doing it, Scrooge. Your days are numbered.

And they are not waiting. They are gathering in their thousands, and their millions.

Demanding work and wages.

Fighting hunger.

Demanding the release of their comrades. Hunger has not crushed, not will prisons daunt them.

They are gathering Scrooge…

I hope you had a rotten Chrismas, Scrooge!

And I hope next year sees you warmer–in hell–than this.”

“Mr. Scrooge–1932,” The London Daily Worker

Translations

Translations are the most common adaptation. Like most of Dickens’s books, A Christmas Carol has been translated into many languages.

| Afrikaans | Esperanto | Japanese | Serbo-Croatian |

| Arabic | Eskimo | Korean | Spanish |

| Braille | French | Lithuanian | Slovack |

| Bengali | Finnish | Norwegian | Slovene |

| Bulgarian | German | Portuguese | Swedish |

| Chinese | Georgian | Polish | Turkish |

| Czech | Greek | Persian | Tamil |

| Catalan | Hungarian | Rhaeto-Romanic | Welsh |

| Dutch | Italian | Russian | Zulu |

| Danish | Irish | Rumanian |