This article originally appeared in the UCSC Review (Spring/Summer 1986; Vol. 11, No. 3). Written by Karen Rhodes. Photo by Shmuel Thaler. Republished with permission from Special Collections and University Relations.

"In the British theater today, Charles Dickens rivals William Shakespeare in popularity," says John Jordan, associate professor of literature at UC Santa Cruz. As Jordan is codirector of the Dickens Project, his claim is a partisan one. Yet the facts back him up.

"In the British theater today, Charles Dickens rivals William Shakespeare in popularity," says John Jordan, associate professor of literature at UC Santa Cruz. As Jordan is codirector of the Dickens Project, his claim is a partisan one. Yet the facts back him up.

The Royal Shakespeare Company's colossal dramatization of Nicholas Nickleby is about to tour again. And last fall, the BBC stages Bleak House (also shown on PBS's "Masterpiece Theatre") "partly as a comment on Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's economic policies," say Jordan.

This summer, the Dickens Project, a multi-campus research effort headquartered at UCSC, will follow the British lead by devoting its annual conference to "Dickens, Shakespeare, and the Theater." Jordan says it will be the Project's most ambitious undertaking in it's five-year history.

"It will involve not only Dickens devotees but also the large number of people who love Shakespeare in particular and English drama in general," says Jordan. "And it will profit from the participation of an international body of scholars and performers."

On hand for the August 7-10 event at Kresge College will be members of the Royal Shakespeare Company's Nickolas Nickleby troupe, including leading actors Roger Rees and David Edgar, who adapted Dickens's novel for the stage. Invited guests will take to the stage as well as the podium for the three-day program of reader's theater and other performances.

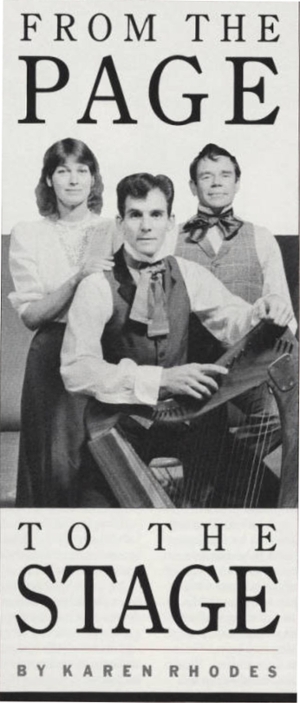

In the spotlight will be the Dickens Project's own Dickens Players (pictured above), who have introduced a fresh approach to the theatrical treatment of Dickens. "Usually, dramatic readings of Dickens don't preserve his exact wording," says Jordan. "We've discovered that his language works theatrically whether it's in the novel or onstage. We're able to keep faithfully to the text without sounding pedantic."

The troupe–players Kate Rickman, Robert Fenwick, and Simon Kelly and musician Gene Lewis–has dramatized such Dickens classics as Mr. Tupman's hilarious proposal to Miss Wardle in Pickwick Papers and Pip's first experiences of love and self-hatred in Great Expectations.

The notion of playing Dickens as he was writ may seem novel, but in fact it pays homage to Dickens's own intentions for his writing, says Jordan. As a young man Dickens had nearly become a professional actor, and he retained a lifelong love affair with theater of all kinds.

"His fiction is intrinsically dramatic," says Jordan. "He even composed dramatically. His daughter Mamie told of an occasion when she was allowed into her father's study to watch him work. He would often dash from his writing desk to a wall mirror, where he would gesticulate and mumble wildly, and then dash back to his desk with a new characterization."

Late in his writing career, Dickens's hankering for the footlights led him to the public-reading circuit. Over a period of almost sixteen years, he gave almost 500 dramatic readings throughout Britain and the United States. These were no mere recitations but elaborate performances that made him one of the biggest box-office draws of the Victorian age.

And since his own time, Dickens's novels have been adapted for countless stage, radio, film, and television dramatizations. In 1935, W. C. Fields achieved a lifelong ambition by portraying Mr. Micawber in a film version of David Copperfield.

Such adaptations have helped Dickens become as popular as England's other great writer–William Shakespeare. Participants in this summer's conference will look at the many similarities between the two writers: the use of melodrama, the double plot, the soliloquy, the exploration of the psyche, the range from burlesque to tragedy, and the remarkable secondary characters.

In fact, if it weren't for Dickens, we might have a different understanding of Shakespeare today, notes Jordan. After Shakespeare's time his plays were subjected to considerable modification, particularly by eighteenth-century classicists who were offended by "weighty" tragic endings. During the Victorian times, Dickens did much to restor the authentic Shakespeare. He helped stage a long-dormant version of King Lear that reinstated the deaths of Lear and Cordelia.

"In many ways," says Jordan, "Dickens is indeed the Romantic Shakespeare."