This article was originally published on the Davis Humanities Institute website as a featured story. Written by Cordelia Ross, DHI Graduate Student Researcher and doctoral candidate in the Department of English at UC Davis. Photos by the Davis Humanities Institute.

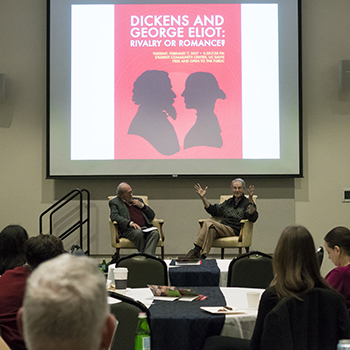

Are you team Dickens or Eliot? That seemed to be the question of the night on Tuesday, Feb. 7, when Dickens Project Founders John O. Jordan and Murray Baumgarten, University of California, Santa Cruz, Director of the Dickens Project and professor emeritus of literature respectively, visited the Student Community Center at UC Davis to talk about Charles Dickens and George Eliot in anticipation of this year’s annual Dickens Universe conference.

Are you team Dickens or Eliot? That seemed to be the question of the night on Tuesday, Feb. 7, when Dickens Project Founders John O. Jordan and Murray Baumgarten, University of California, Santa Cruz, Director of the Dickens Project and professor emeritus of literature respectively, visited the Student Community Center at UC Davis to talk about Charles Dickens and George Eliot in anticipation of this year’s annual Dickens Universe conference.

Sponsored by The Dickens Project, a multi-campus research unit of the University of California, this year’s Dickens Universe conference will feature for the first time a text by another author, George Eliot’s Middlemarch. The conference, a weeklong event held at UC Santa Cruz, will be held between July 30-August 5, 2017 and registration is open to scholars, teachers, students, and members of the general public. Undergraduate students also have the opportunity to receive 5 units of UC credit if they enroll in a course offered concurrently with the conference.

Ensconced in comfy armchairs (sadly the fireplace with crackling logs alit could not be provided), Jordan and Baumgarten plunged into Victorian England’s literary culture, referencing letters the authors exchanged privately, those they published publicly about each other, and reviews and letters their peers published about them.

Advertised as a “free-wheeling” conversation, Jordan and Baumgarten led the room in a lively discussion, welcoming audience insight and relishing opportunities to engage in a bit of Victorian literary gossip.

Advertised as a “free-wheeling” conversation, Jordan and Baumgarten led the room in a lively discussion, welcoming audience insight and relishing opportunities to engage in a bit of Victorian literary gossip.

First they sketched out a brief biography of the authors and their lives. Dickens, one of the most influential authors of his day, had been a well-known and successful novelist for about 20 years before Eliot appeared on the scene.

A nom du plume, George Eliot was actually Mary Anne Evans, who chose to write under a male name so that bias against her gender would not affect her standing as an author or influence the reception of her work. Her identity remained a secret for a few years until a man, Joseph Liggins, tried to take credit, thinking to capitalize on the success of her novel, Adam Bede. Eliot–or Evans–was forced to reveal herself, which thankfully did not damage her reputation as an author and she continued to write and publish.

After discussing Dickens’s and Eliot’s literary origins, Jordan and Baumgarten proceeded to discuss the nature of the relationship between Dickens and Eliot as literary peers and rivals. Their banter alternated between a question of romance or rivalry. Circumstances had forced the younger and female Eliot to create a cultural space for herself in a field dominated by men, and she did so by taking on the role of rival to Dickens. But, as Jordan and Baumgarten, pointed out, she did so while remaining aware of Dickens’s mastery of the form and harboring a deep respect for him.

Dickens, on the other hand, though frequently critical of his literary contemporaries was surprisingly impressed with Eliot and even wrote to her personally in the early stages of her career expressing his admiration for her work. Captivated by her artful and complex stories and characters, he asked in the letter if perhaps Eliot was a woman because he believed “that no man ever before had the art of making himself, mentally, so like a woman, since the world began.” Simply curious and not wishing to “out” her, he ended his letter with “I shall always hold that impalpable personage in loving attachment and respect, and shall yield myself up to all future utterances from the same source, with a perfect confidence in their making me wiser and better.”

Dickens, on the other hand, though frequently critical of his literary contemporaries was surprisingly impressed with Eliot and even wrote to her personally in the early stages of her career expressing his admiration for her work. Captivated by her artful and complex stories and characters, he asked in the letter if perhaps Eliot was a woman because he believed “that no man ever before had the art of making himself, mentally, so like a woman, since the world began.” Simply curious and not wishing to “out” her, he ended his letter with “I shall always hold that impalpable personage in loving attachment and respect, and shall yield myself up to all future utterances from the same source, with a perfect confidence in their making me wiser and better.”

Ironically, it was that very issue of characterization that Eliot used to set up her rivalry with Dickens, arguing his characters lacked “psychological interiority.” Both Jordan and Baumgarten thought this was an unfair critique of his work, arguing that it was only applicable to some of Dickens’s characters, but not all. They were more intrigued by the fact that Dickens seemed to understand that Eliot could so expertly offer something he could not: a woman’s perspective. What could a woman writer see in Victorian culture that Dickens could not?

A woman “living in sin” with a married man, Eliot could offer a great deal. Her success as a novelist broke down traditional social barriers and even protected her from later personal scandals. When she eventually married, her 20 years younger husband purportedly jumped out of the window and into the canal when they were honeymooning in Venice. No one knows why. People have speculated that he couldn’t handle her sensuality, a speculation applicable to Dickens’s relationship with women–at least his literary one, though his weird fascination with his deceased sister-in-law and much later affair with a teenaged actress hint at larger issues. Dickens’s female characters more so than many others lack the psychological interiority of any of Eliot’s characters.

While the question of gender and sexuality remained the focus of the evening, Jordan and Baumgarten also considered criticism against Dickens’s scientific knowledge. Several of his literary and scientific peers were upset at the scene of spontaneous combustion in Bleak House. And others were appalled by the state of Dickens’s own library! Apparently, it was unimpressive for such a prolific writer.

From bits of gossip to analysis the evening drifted on and by the end Jordan and Baumgarten concluded that while Eliot’s work falls under the umbrella of realism, it was unfair to expect the same of Dickens. He was, they decided, a Victorian predecessor to the idea of magical realism. He could have completely unreal characters who lacked depth and he could have spontaneous combustion because he was more interested in the art of storytelling than in realism. And they concluded that Dickens’s letter to Eliot is the romance in the rivalry and should be read as a kind of love letter.