In writing of Michael Slater’s biography Charles Dickens, a popular sell-out at the University of Oregon bookstore, Dave Masko points out that Slater “writes that Dickens [on his visit to the United States in 1842] was ‘amazed’ at the ‘worship’ or ‘celebration of this pagan festival called Halloween.’” While Masko acknowledges that Dickens shared with Halloween celebrants a fascination with ghosts, he asserts that Halloween was not celebrated in Dickens’s day.

HOLD ON

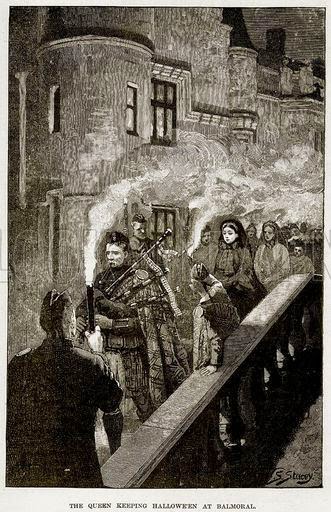

Google “Halloween in Victorian England,” and you will find that Queen Victoria loved celebrating Halloween at Balmoral Castle. Behind her royal carriage a procession carrying lighted jack-o’-lanterns marched to a giant bonfire. As bagpipes played, an effigy of a witch — or, at times, one of Victoria’s perceived enemies — was thrown into the blaze, after which celebrants enjoyed refreshments at the castle. In 1874, the crowd got out of hand and the festivities at the castle had to be cancelled.

Victoria was not alone in celebrating. The Victorians enjoyed Halloween traditions familiar to us today as well as traditions not at all familiar.

They carved both pumpkins and turnips to ward off evil spirits and to use as lanterns. They enjoyed caramel apples, sweets, and roasted nuts. They wore simple costumes, donning black capes to which they might add bat wings. They told ghost stories, held seances, and bobbed for apples. They were fascinated by headless photographs and spirit photography. And they enjoyed parties. Finding a carved pumpkin on one’s doorstep was a cause to rejoice that one was invited to a party.

One particularly ghoulish party activity unique to Victorians was “unwrapping.” At an unwrapping party guests joined in the dubious pleasure of unwrapping a mummy — an actual mummy supplied by Egyptian exporters. Some of these mummies were quite “fresh” since poverty-stricken Egyptians found that selling the body of a deceased relative augmented their meagre means.

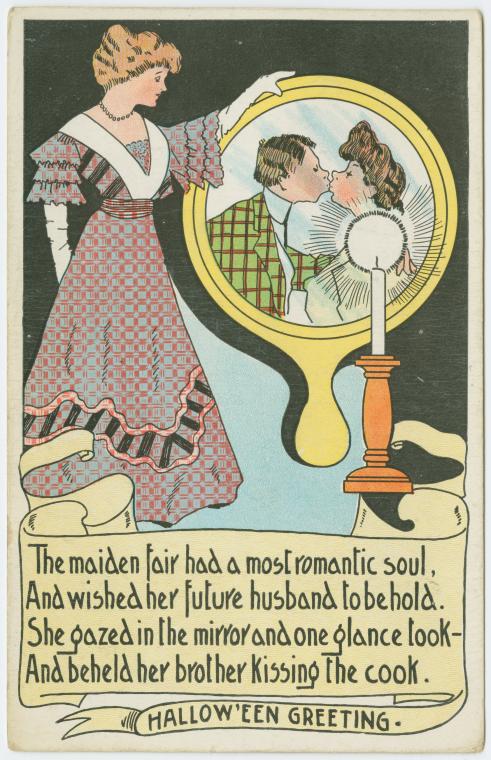

However, by far the most popular party activities involved revealing marital prospects. There were several traditional ways that young people might discover their prospects. Most common was the serving of slices of fruit cake or a Barmbrack cake — an Irish yeast bread with sultanas and raisins — which contained buried tokens: a ring, a coin, and a thimble, needle, or button. Finding a ring in one’s slice of cake foretold marriage within a year. A coin promised wealth. A thimble, needle or button consigned the recipient to spinsterhood or bachelorhood. Another way of determining one’s marital prospects involved the use of three bowls and a blindfold. One bowl contained clear water; another, milky water; and a third, no water at all. A young volunteer was blindfolded and led toward the three bowls with the instruction to reach out with his/her left hand. Dipping the hand into the bowl with clear water prophesied marriage to a bachelor for a woman or a maiden for a man. Dipping the hand into the milky water signified marriage to a widower or widow, and the empty bowl indicated a single life. Finally, standing before a mirror in a darkened room could also reveal the future for a woman. She might see the reflection of the man she would marry. However, if she saw a skeleton she would be a spinster.

So, yes, Halloween was celebrated in Victorian England. In fact, the origins Halloween go back centuries to the Celtic celebration of Samhain, a festival held in Ireland and Scotland at the end of harvest time and the beginning of Winter. It was originally a sort of New Year’s that marked a time when those of this world and those of the “otherworld” — dead souls — were open to each other. Celebrations centered around costumes and bonfires to ward off evil spirits. Some claim that the tradition of “trick or treating” can be traced back to medieval Briton and Ireland. “Soulers” — mostly children and poor people — went with songs and prayers to the homes of rich people, who gave them “soul cakes” — round spiced cookies containing raisins and marked with a cross on top.

Thus Halloween’s origins are pagan. But then in the 8th Century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as the date to honor all saints and October 31 became the “hallowed” evening that preceded All Saints Day as well as All Souls Day — an example of a historical adaptation of two cultures to each other.

A closing note: “Adaptation” continues. Opening on October 30, 2022, at the Renaissance Theatre in Orlando, Florida — A HALLOWEEN CAROL, a frightful new musical that is a retelling of Dickens’s classic by Tracey Janes.