View of the Monterey Bay from Cowell College

View of the Monterey Bay from Cowell College

Stevenson and Cowell College on the University of California, Santa Cruz, campus saw a gathering of 275 people the week of August 15-21 for the 38th Dickens Universe, this year focusing on Little Dorrit, Dickens’s twelfth novel. The assemblage was treated to cool, foggy mornings and warm, sunny afternoons under the redwoods, as well as a stupendous view from the hill of the campus meadows and the Pacific Ocean.

Graduate students and faculty arrived on campus Saturday, July 14, and the general public, Elderhostel attendees, and high school, community college, and undergraduate students started their week on Sunday. The conference also comprised the fourth week of an NEH Summer Program for the Humanities conference for high school teachers titled “Why Literature Matters: Voices from Nineteenth-Century Britain and America.”

After everyone was settled in their rooms and had had dinner in the Cowell Dining Hall, the group moved to the Humanities Lecture Hall, where Dickens Project Co-Director Renee Fox welcomed them, saying that she started attending the Universe as an undergraduate student, and that her continued work with the Dickens Project through the years has been important in her academic career. Nearly fifty universities are now members of the Dickens Project Consortium, she said, and their current work centers on ways to make Victorian literature meaningful in today’s world. One of the things that make this week special, Fox said, is the “power and purpose in a group of people making time to think together.”

Post-Prandial Potations

Post-Prandial Potations

Fox introduced the Project staff, Assistant Director Courtney Mahaney and Program Assistant Nathalie Coletta; and the program organizers, Jonathan Grossman of UCLA and Helena Michie of Rice University. She also introduced the board members of the Friends of the Dickens Project, the fund-raising arm of the Project, and thanked them for making this week’s program possible. She announced that the Dickens Library was open to visitors (this is the first time the Universe has been held at the campus where the library is housed since it was moved from Kresge College), and she also announced the Neighborhood Academic Initiative’s exhibit “A Walk Home” in the Eloise Pickard Smith Gallery at Cowell College. The exhibit features photographs of walks home by students in Jacqueline Barrios’ AP English class at Foshay Learning Center in Los Angeles, and the students’ poetry about their walks, written after working with Little Dorrit.

Jim Buzard of MIT presented Sunday evening’s lecture, “Liquid Dorrit,” in which he linked both literal and figurative liquidity in a number of forms to situations and characters in the novel. Starting with the contrast of the foul water in the harbor and the clear open sea in the novel’s introduction, Buzard took his audience on a tour of other “liquid” images and ideas—the flow of “nondescript” people going into the Marshalsea in Book 1 Chapter 9 as a “liquid stream of people,” the ocean of the Barnacle family, and other images. Besides the literal bodies of water in the novel, Mrs. General is an example of views and rules that should flow down from her to her charges; Mr. Merdle “oozes” about his drawing room and kills himself in a public bathhouse. “He was nothing more than a drop of the condensed medium” of water, Buzard said. And Rigaud seeps, penetrates into other characters’ lives and business. Buzard concluded his talk with a summary of the story of Dr. John Snow and the outbreak of cholera that Snow insisted could be traced to a single water pump in London in 1848, countering the prevailing belief that cholera was spread by the “miasma” theory of disease, claiming that it was spread by breathing infected air rather than by drinking infected water. Although the novel is set earlier, Buzard claimed that Little Dorrit alludes to this 1848 incident, pointing out that Dickens promoted the prevalent miasma theory in Household Words, and that Little Dorrit contains references to London’s river as a “deadly sewer” and other passages about “waste droppings” and trash at the places where people draw drinking water. “If we posit that Dickens was aware of Snow,” Buzard said, “we read the passages differently.”

Each evening after the lecture, the BBC’s Little Dorrit: Nobody’s Fault and Little Dorrit’s Story, with Derek Jacobi as Arthur Clennam and Alec Guinness as Mr. Dorrit, were shown in the Humanities Lecture Hall for those who were able to remain awake.

19th-Century Seminar Participants

19th-Century Seminar Participants

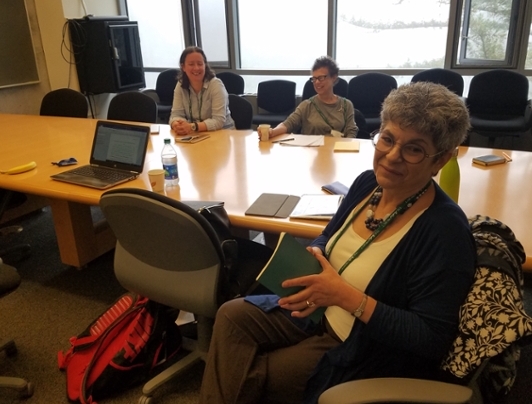

On Monday morning after breakfast, members of the general public attended group discussions led by faculty members. Your correspondent was lucky to be assigned to the group led by Elizabeth Meadows of Vanderbilt University. Other groups were led by Alison Hedley of Ryerson University; Gerhard Joseph of CUNY and George Levine of Rutgers; and David Agruss of Arizona State University. Also at this time the “19th-Century Seminar” was held. This seminar allowed selected “independent” scholars, or those who are not affiliated with the Dickens Project Consortium, to present their in-project work, on Dickens or other 19th-century topics, to a group led by two Dickens Project faculty members. Graduate students also attended presentation and writing workshops, which are unique opportunities for future university faculty members to gain experience not usually included in their graduate curriculum.

On Monday morning, Daniel Stout of the University of Mississippi read his paper titled “Little, Maybe Less—Dickens’s Vanishing Points.” He started out by saying, “I want to start by thanking the miracle that is the Dickens Project for existing in the first place.” He then went on to call his audience’s attention to a pre-Little Dorrit essay written by Dickens titled “Gone to the Dogs,” published in Household Words. In this essay, which Stout noted is not included in the current Penguin edition notes for the novel, Dickens argued that “Posterity has gone to the dogs,” and described those dogs as the “dogs of decline” and the “dogs of war,” referring to the Crimean War and specifically to the British government’s mishandling of the Siege of Sevastopol. The essay, Stout said, “does us a favor by distinguishing the dogs,” and, he said, establishes Dickens’s desire to establish “fault,” or accountability.

No one, Stout continued, can say where the “diminishment” of government accountability begins, as evidence by the Circumlocution Office and Dickens’s first title for Little Dorrit, “Nobody’s Fault.” Critic Lionel Trilling wrote of the “emphasis on personal responsibility” in the novel, but Stout disagrees. Little Dorrit, rather than being a novel about people who see the world as it is and make an effort to find out whose fault it is and how to fix it, is a novel made up of “ended characters in an ended world.” The novel does not, then, ask questions about how to keep the world from going to the dogs; it rather asks, “How do we live in a world that’s already gone to the dogs?” Although there are those who try to take responsibility (Clennam goes to jail, Pancks engages in “endless accounting,” Mrs. Clennam will “never forget”), Stout argues that “It’s pointless to demand accountability.” The title of Dickens’s last several chapters tell the story: “Going,” “Going,” “Gone,” and “turn the novel into a vanishing point,” Stout said.

Faculty-Led Graduate Student Seminar

Faculty-Led Graduate Student Seminar

After the morning lectures, attendees from the general public again broke into discussion groups, led by graduate students. The difference between the early morning groups and the mid-morning groups is that the first groups concentrate on the context of the novel—what was going on in Victorian society at the time Dickens wrote the novel and at the time he set it. The graduate student groups focus on discussing the text itself, although these purposes often overlap. Also at this time, a yoga class was offered, NEH Summer Seminar attendees continued their meetings, and Project faculty members conducted their own seminar.

And, after lunch, the busy schedule continued, with faculty-led seminars for graduate students and for undergraduate, high school, and summer session students. Twenty undergraduate students attended the Universe this year, from colleges including Amherst College, University of Delaware, Kalamazoo College, University of Maryland and UCSC, in addition to the Community College Scholarship winners, from De Anza College and College of the Redwoods, respectively. The writing workshop for these students was led by Julie Minnis of the Friends of the Dickens Project and UCSC graduate student Tara Thomas. On Tuesday and Wednesday, the conference offered field trips. Tuesday’s outing featured the recently donated Grateful Dead Archive and the other Special Collections at the McHenry Library; on Wednesday, there was a tour of the Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. For members of the general public who had not had their fill of Dickens, this early afternoon time slot also offered “Dickensian Seminars,” led by long-term Universe attendees Wayne Batten, David Brownell, and Christian Lehmann.

Tea Punch served daily during the Victorian Tea

Tea Punch served daily during the Victorian Tea

At 3:00, the popular Victorian Teas were presented by the Friends of the Dickens Project outside the vintage ‘70s Stevenson Café, which was closed for the summer. The venue offered something the teas had never had before—small tables and chairs set out on a terraced patio under towering redwoods, which delightfully complemented the silver tea service, flowered tablecloths, china cups, hot Earl Grey tea, cold ginger-tea punch, fresh strawberries, and home-made tea cookies that returning attendees have come to expect. At the same time, the rehearsal for the week’s farce was being held in the adjacent Stevenson Event Center, which provided a piano accompaniment for the tea drinkers.

At 3:45 each day, the Universe’s pro-tem master of ceremonies, Christian Lehmann, announced in his theater-worthy baritone that the 4:00 talks would start in the Humanities Lecture Hall up the hill. On Monday, Courtney Hopf of New York University, London, presented “The Streets and Spaces of Dorrit”; on Tuesday: the Dickens Project’s Digital Coordinator and NAI Liaison Jon Varese, author of the recently published novel The Spirit Photographer, talked about his book in a question-and-answer format with Daniel Novak of the University of Mississippi. A book signing followed this talk, with books available for purchase outside the lecture hall (they sold out!). On Wednesday and Thursday afternoon, panels were presented in the Humanities Lecture Hall: Jason Rudy of the University of Maryland and Tricia Lootens of the University of Georgia discussed “Which Victorians? Whose Victorianism? Race, Slavery, and an Opening Universe” on Wednesday, on a panel moderated by Ryan Fong of Kalamazoo College. On Thursday afternoon, Carolyn Dever of Dartmouth College, Jill Galvan of Ohio State, and Grace Lavery of UC Berkeley made up a panel on “Power in the Academic Profession: Intersections of Gender and Race.” Also at 4:00 throughout the week, graduate student training continued, with a pedagogy workshop and a publication workshop. Undergraduates and high school students attended writing workshops.

Deciphering Dickens Project

Deciphering Dickens Project

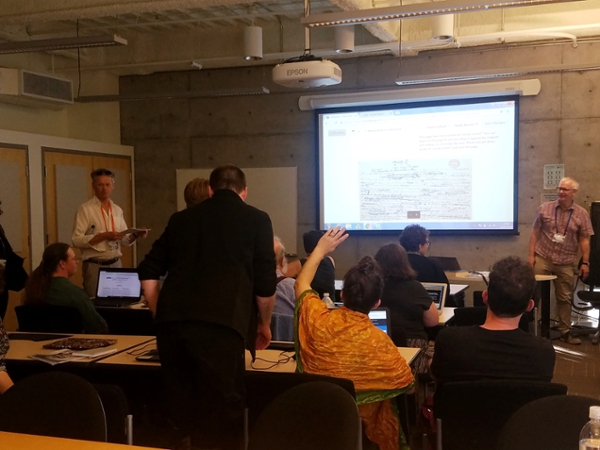

At 5:15, a special seminar titled “Deciphering Dickens” was presented by Douglas Dodds, senior curator in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Word and Image Department; and John Bowen, of the University of York. These two researchers are asking the public’s help in deciphering some of the less readable portions of the massive number of manuscripts Dickens left behind—numerous drafts, proofs, and other plans for his novels. Their plan is to eventually make the deciphered material widely available in digital format. If attendees were up for more afternoon activity before dinner, Victorian dance lessons were offered by Annie Laskey to prepare people for the Friday night dance.

After dinner, the ever-popular post prandial potations were served by graduate students in the patio outside the Humanities Lecture Hall, where attendees were also treated to a daily silent auction, book sales, and later in the week T-shirt and sweatshirt sales.

California Community College Scholarship Recipients, Kaylee Steiner and Allen Lue with scholarship founder, Tom Savignano

California Community College Scholarship Recipients, Kaylee Steiner and Allen Lue with scholarship founder, Tom Savignano

On Monday evening, Dickens Project Director John Jordan introduced this year’s scholarship winners. Community college winners were Allen Lue of DeAnza College in Cupertino, whose winning essay was titled "An Inductive Analysis of British Imperialism in Jane Eyre"; and Kaylee Steiner of College of the Redwoods in Eureka, whose essay title was "Napoleon and the Destroyer: Money and Status as Motivating Forces in Tono-Bungay." There were six high school scholarship winners from Foshay Learning Center in Los Angeles, only two of whom were able to attend the Universe. The winners were Sabina Mendoza, whose paper was titled "I Protest: An Analysis of Frederick Dorrit’s Agency in Dickens’s Little Dorrit"; Andrew Oropeza, whose paper was titled "Broken Sounds: Mr. Dorrit’s Interrupted Speech in Charles Dickens’s Little Dorrit"; Jasmin Sanchez, whose paper was titled "A Humble Love: Class and Feelings in Dickens’s Little Dorrit"; Keyrin Velasquez, whose paper was titled "Running to No Avail: A Comparison of Mr. Dorrit and Mr. Merdle in Charles Dickens’s Little Dorrit"; Angie Veliz, whose paper was titled "Penetrable Impenetrability: The Statue-like Mrs. Clennam in Charles Dickens’s Little Dorrit"; and Alyssa Young, whose paper was titled "To Rave About Amy: The Big Outbursts About Charles Dickens’s Little Dorrit.” These high school students write papers after studying Little Dorrit in their AP English class, which is taught by Jacqueline Barrios, who also attended the Universe. They are part of the Neighborhood Academic Initiative, which several years ago entered into a partnership with the Dickens Project facilitated by Jon Varese. The NAI shepherds at-risk students from largely Latino neighborhoods in East Los Angeles through their 12 years of schooling at the same school, which has lowered dropout rates. By enlisting the help of nearby USC and the students’ families, NAI has been successful in transitioning these students to college and beyond. Sabina Mendoza will study accounting at USC this fall; Andrew Oropeza will start his work in narrative studies and music at USC; Jasmin Sanchez will major in Health and Humanity at USC; Keyrin Velasquez plans to major in Human Biology at USC but is also thinking about English/Classics; Angie Veliz will major in biology at UC San Diego; and Alyssa Young is looking at philosophy, political science, law and accounting programs at USC. Andrew Oropeza and Angie Veliz were the two students who were able to attend the Universe this year.

Dickensian Seminar participants

Dickensian Seminar participants

After the introduction of the scholarship winners, The Herbert Furse Memorial Lecture was presented by Sharon Aronofsky Weltman, Louisiana State University. Her title was “The Littleness of Little Dorrit.” Weltman, who is diminutive herself, started by pointing out that the idea of femininity in Victorian literature is often realized in a small woman, which echoes women’s constrained roles. There are differing arguments about Amy’s height and size, and these arguments, Weltman said, can co-exist. Little Dorrit, she said, is, after all, about “perception, misperception, and point of view.” Is Amy’s growth stunted because of early malnutrition? Does she starve herself to make sure her father has enough to eat? Does Dickens mean to portray her as disabled in some way? First, Weltman said, Amy is not small due to malnutrition or neglect. Her mother did not die until Amy was eight, so there is no evidence that she was denied mother’s milk and her mother’s love. Plus, the Marshalsea is a family, and they care for her. Weltman also refuted the second claim, that Amy starves herself. She doesn’t bring home all of the food that’s given to her as part of her pay. She eats some of it—enough to keep herself notably healthy, as she is never ill. Most likely, Weltman said, what her employers considered a normal portion of food is too much for her to eat because of her size, so she brings home what she can’t eat. Is Amy’s size meant to portray her to be disabled or disfigured in some way, and is she “sexless”? Weltman says no. Amy has the body of a woman; she is just small. Clennam refers to her as “childlike,” and it is true that others see her as different; she is “pointed out to everyone” in the novel. Weltman believes other characters in the novel underestimate her, as does Clennam, at least at the start. Amy has a “disquieting effect” on others, such as the streetwalker who is startled to realize that Amy, not Maggie, is the woman. Dickens, then, “considers what it feels like to be a very small woman,” Weltman concluded, and “to be perceived as she was.” We do, she said, “need to pay attention to stature as physical phenomenon.”

Graduate Student Presentation Workshop

Graduate Student Presentation Workshop

On Tuesday morning, Cornelia Pearsall of Smith College spoke on “Little Dorrit’s Dead Letter.” She started with the end of Jane Eyre, when Jane and Rochester experience a supernatural form of communication: he calls her name three times, and she, miles away, hears him and comes to him. But Jane never tells her husband about this experience. She and Amy thus both keep personal information from the men they are to marry—why? Jane at least explains her decision by saying the experience was “too inexplicable to be discussed.” But Amy offers no such explanation. Arthur, when he is asked to burn the unread papers, does not ask what they are. The iron box in Little Dorrit is, Pearsall said, in effect a dead letter office, and dead letter offices did, eventually, burn letters. But letters, she said, like written wills, have a number of stops to make, any one of which can result in a loss of the information they contain: they need to be written, delivered, received, read, and interpreted correctly. And, then, people don’t always respond to them. Examples are Arthur’s mother’s letters, and Amy’s letters to Arthur. The concept of an “archive” comes into play here, Pearsall said, in this case, the codicil. It moves through a chain of events, but ultimately, Amy keeps the “archive” closed, even after his demands at the start of the novel that “I want to know.” He is, Pearsall said, looking in his mother’s house “for something else for someone else, but he’s really looking for the iron box.” Affery, while she has been “right in her facts but wrong in her theories,” also doesn’t realize that the ghost in the Clennam house is Arthur’s mother the letter writer, still writing, still marking the walls with “long crooked touches, when we are all a-bed.”

The Tuesday evening lecture was given by Jason Rudy of the University of Maryland, on “Dorrit Down Under.” He said he would “channel Mrs. General” to start (after PPP, he said, his was a Perfect Privilege to Present), and indeed the sections of his lecture were titled, “Papa,” “Potatoes,” “Poultry,” “Prunes,” and “Prisms.” His lecture, he said, would be a “historical excursion temporarily away from Little Dorrit,” yet he kept the novel at the front of his audience’s minds by pointing out that had John Dickens stolen the bread that put him in debtor’s prison rather than incurring a £40 debt to the baker, the Dickens family would have been deported to Australia rather than being imprisoned in the Marshalsea. From this jumping-off point, Rudy proceeded to give his audience a fascinating history of deportation from England to Australia and of the emigration of non-prisoners when gold was discovered there, arguing that Australia was “a land of contrarities.” The “topsy-turvy” country, as it was called in a popular publication, The Leisure Hour, echoes the contrarities in Dickens’s novel—poverty and riches, the “nose down, mustache up” identification of Rigaud, the up and then down Merdle scheme, appearances and disappearances throughout the book. These reversals in Dickens represent, he said, “antipodean thinking.” Rudy then entered the “what if” portion of his paper: what if Dickens had been thinking of emigrating to Australia at the time he was writing Little Dorrit? “Australia was definitely on Dickens’s mind,” Rudy said, citing a letter to Forster in which Dickens states he has a “slight idea” of moving to Australia, but not until after he had finished Little Dorrit. Reading the novel with this possibility in mind, Rudy said, reveals a novel rife with veiled references to transport and emigration—the possibility of escape rather than imprisonment, Amy on the iron bridge thinking about “distant masts,” Clennam’s early life spent in a form of transportation. “Exile, home and belonging may seem different in Little Dorrit if we think about Australia,” Rudy argued. Yet, he said, Dickens “wants to land us back at our own doorstep. He wants us to appreciate the modesty of staying at home.”

Undergraduate and High School Student Writing Workshop

Undergraduate and High School Student Writing Workshop

On Wednesday morning, Peter Logan of Temple University spoke on “Victorian Madness: Moral Insanity and Little Dorrit.” Logan posited that Little Dorrit contains three types of madness that Victorians knew about but that post-Freudians don’t recognize. Although there are few actual episodes of madness in the novel, he said, the Victorian reader would have recognized characters who were “eccentric,” which had a different definition from ours; those who suffered from “moral insanity”; and those who suffered from “intellectual insanity.” Dickens consciously included examples of all three types.

Eccentricity to the Victorians was not a deep-seated problem but was represented by, Logan said, actions without motivation. These actions in Dickens take the form of tics, for which his characters are famous. Little Dorrit contains “light eccentricity,” but Dickens’s later novels contain what Logan called “darker eccentrics.” The second form, moral insanity, was proposed by Dr. James Prichard at the time Dickens started his writing career in 1833. People suffering from moral, or emotional, insanity had “a morbid perversion of the natural feelings, affections, inclinations, temper…”, according to Prichard, a list that could be widely interpreted. However, Prichard claimed, these people did not suffer from delusions or hallucinations, something that was discussed widely in the Victorian press. Intellectual faculties were not affected by moral insanity, but those who were suffering from the third form, intellectual insanity, could suffer hallucinations or delusions.

Logan further classified Little Dorrit’s characters by putting them into three groups: those who have motivation but do not act; those who have motivation and do act; and those who act without motivation. Clennam is motivated to act and does act, removing him from any definition of insanity. Mr. Plornish’s mimicry of his wife’s words has no motivation and thus become a tic, making him an eccentric. But Tattycoram, Logan argued, is “one of Dickens’s most inexplicable characters,” in that she not only has tics and thus can be classified as eccentric, but she also acts without motivation and can be classified as suffering from intellectual insanity. Logan posited that there is no other reason for Tattycoram’s presence in the novel other than to round out the novel as “psychologically realistic” given the Victorian understanding of psychology, which in turn, he said, “poses new questions about nineteenth-century realism.”

Wednesday evening was free, allowing attendees to rest, visit Santa Cruz’s downtown area, or catch up on reading. On Thursday morning, Sukanya Bannerjee of the University of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, presented a lecture titled “Writing Bureaucracy, Bureaucratic Writing.” The Circumlocution Office in Little Dorrit, Bannerjee said, was modeled on the Treasury Office. There was a heightened interest in bureaucracy in mid-Victorian England, she said, largely because of the investigations spurred by the blunders made during the Crimean War. However, she wanted her audience to know that her paper does not take this ineptness for granted; rather, she offers a “more layered reading of bureaucracy” by moving away from the bureaucratic and toward the literary. Dickens, she said, was “engaged in bureaucracy” while he was writing Little Dorrit, and he published a number of “takedowns” of the bureaucracy in Household Words. But he actually moves away from bureaucracy in Little Dorrit, just as he moved away from his original title. Despite the Circumlocution Office, the Dorrits are freed, and Arthur and Amy do get married. Yes, Dickens believed that the bureaucracy had been compromised, but somehow Little Dorrit looks for a way through it, Bannerjee said. The Circumlocution Office does nothing, but what is it that it is supposed to do? Readers are never told. The introduction of the Merdle story actually makes the Circumlocution Office seem less destructive. In a sense, she went on, Little Dorrit may “make a muted case for bureaucracy.” There is a recognition of bureaucracy’s “deadening effects” in the novel, but that recognition in turn “makes space for bureaucratic sensibility.” As a “coda” to her talk, Bannerjee showed an image of the ornate “Writers Building,” which still stands in Calcutta and is referred to as “The Writers.” It is thus at once a reminder of the bureaucratic power that ruled India during Dickens’s time and a link between bureaucracy and writers. And, she argued, a case for bureaucracy is made here, too. “By gaining entry to bureaucracy, the Nationalist Movement in India was born,” she said.

Performance of "Everybody's Fault" by Dickens Universe participants

Performance of "Everybody's Fault" by Dickens Universe participants

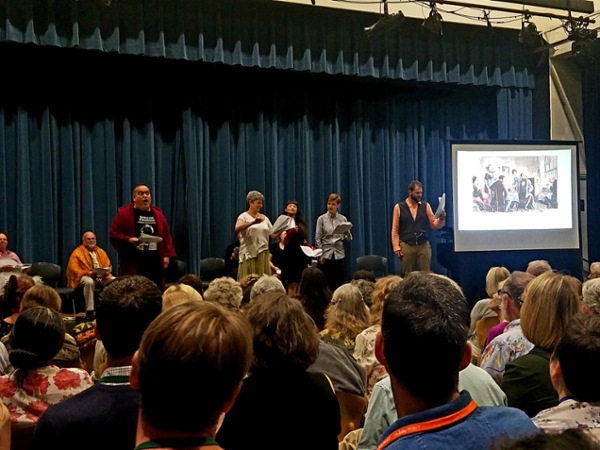

On Thursday evening, a farce titled “Everybody’s Fault: A Dickensian Travesty” was presented in the Stevenson Event Center. Written by Adam Abraham of Virginia Commonwealth University, the play was, amazingly, cast on Monday afternoon from volunteer conference attendees (including a piano player), rehearsed for four days, and presented (almost) seamlessly on Thursday night. This year, the play’s vehicle was a young couple settling in for the evening: “Nothing can be done,” one of them says. “Let’s watch Netflix.” As they run through the list of offerings by genre, they come to a family comedy called “The Dorrit Family.” To the tune of the old “Addams Family” theme song (reworded, of course), the family is introduced, with special guest star Arthur Clennam. The family members are so bizarre that the young couple look for something else— how about “50 Characters in Search of an Author”? In this one, Mr. F’s Aunt spouts, “Spiro Agnew was the 39th vice president,” and Flora, wonderfully portrayed by Frances Laskey, sings “I think I did it again” to the tune of Britney Spears’ “Oops, I Did It Again.” “I like it,” says one of the viewers, “but I wouldn’t binge it. What about ‘The Circumlocution Office’?” In this show, Doyce and Clennam are portrayed trying to make their way through a crowd of people to each other. “Let’s go back to ‘The Dorrit Family’.” The next episode is “Mr. Dorrit Released.” Mrs. General sings “I am the very model…”. Mr. Dorrit has his breakdown, but Mrs. G. corrects him from “I am the father of the Marshalsea” to “I am the Papa of the Marshalsea.” The viewers switch to the Hedgehog News, which is covering the financial crisis of 1857. Fagin, Micawber and Ponzi make up a panel. Fagin sings, “In this life, one thing counts…”, Mr. Micawber promises that something will turn up. Mr. Merdle walks up to the panel, borrows a pen, and falls to the ground. The next choice of show is “Nobody’s Fault.” The viewers complain that “it keeps coming back to Arthur Clennam.” They try to turn it off but can’t, so they ask the actors, who respond, “Would you like to sing about it?” and break into “We’re living here in Dickensland, with more characters than anyone planned,” to the tune of Billy Joel’s “We’re Living Here in Allentown.” The farce concluded to a standing ovation.

Grand Party

Grand Party

This year, the Friends of the Dickens Project were able to set up their Grand Party, which included a wine and beer bar, cakes, cheeses, and other delicacies, in the room adjacent to the room that served as a theater, so there was no travel time between the farce and the party. Attendees took full advantage, and the evening was a great success.

Friday morning’s lecture, the last of the week, was given by Kathleen Frederickson of UC Davis, and was titled “The Wade Trade.” Frederickson explored the enigmatic character of Miss Wade, suggesting that Dickens wished to integrate her more fully. She is described as dark, against the “white Englishness” of her fellow characters. There is a hint of an illegitimacy plot, and there are other anomalies that make Miss Wade, and her “trade,” a mystery. For one, her immovability and silence are contradicted by her constant change in lodgings. And, while Dickens clearly describes Affery’s abuse by her husband, there is a noticeable lack of details about the relationship between Miss Wade and Tattycoram. Yet the abuse is the same in that Tattycoram is fearful. Miss Wade is also described as “diseased” in this relationship; she sees her own illness in Tatty. But what is it? She constantly has her hand on her bosom and pinches her neck, “tearing hard.” In the final section of her lecture, Frederickson went further with the idea of disease by saying that Dickens makes a brief reference to harems, and the novel does have travelers returning from the East and being quarantined. Egyptian cotton, she said, was thought to carry plague, but the need for quarantine was being questioned at the time. Thus there is an anomaly here, also, as there is what Frederickson called a “false freedom” in moving out of quarantine, reflected by the fact that Miss Wade and Tattycoram live in England as though they are travellers.

Until next year!

Until next year!

On Friday afternoon, the Project’s Director’s Report was given by John Jordan at 4:45. This report has previously been made to the Friends of the Dickens Project Board, but it contains information that is important to all attendees, especially news about funding and other programs sponsored by the Project. Friday evening has been reserved for a number of years for the Victorian Dance. This year, Annie Laskey, with The Great Expectations Orchestra, led the dance in the Stevenson Event Center. Before those festivities, however, the annual fund-raising auction was held, with Tim Clark as the auctioneer, and the book for next year was announced: Barnaby Rudge. Next year’s Universe is scheduled for July 14-20. Mark your calendars!