Charles Dickens, 1812-1870

Dickens’ Life Before the Carol

In October of 1843, when he started to write A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens was at thirty-one the successful author of Sketches of Boz, The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, and American Notes. Although his previous books had been very popular, with some numbers of Curiosity Shop selling as many as 100,000 copies, his current novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, was only selling about 20,000 per monthly number. His publishers threatened to reduce his salary from £200 to £150 per month. His wife Catherine was expecting their fifth child. As a solution to these financial pressures, Dickens was planning to leave England for Italy, where his family could live more cheaply.

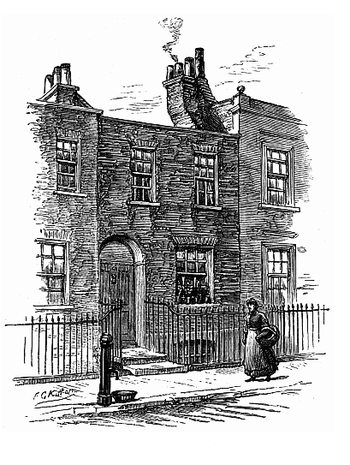

Money had always been a worry for Dickens. He was born into a struggling lower-middle class family. When he was ten, Dickens’s father moved the family from Chatham to a smaller house in Camden Town, London. The four-room house at 16 Bayham Street is supposedly the model for the Cratchits’ house. The six Cratchit children correspond to the six Dickens children at that time, including Dickens’s youngest brother, a sickly boy, known as “Tiny Fred.”

The shorter building is one of several childhood homes of Dickens, this one possibly the model for the Cratchits’.

Even with the move to London, his family could not afford to send Dickens to school, and instead he was free to explore the urban neighborhoods around him. When he was twelve, his father found work for him in a factory, and he boarded with another family, much as David Copperfield boarded with the Micawbers. Soon afterward, his father was imprisoned for debt, and the whole family moved to the Marshalsea debtors’ prison save for Charles, who kept working. He felt abandoned and ashamed of this experience for the rest of his life, and although he fictionalized it in his novels, during his life he told the truth to only one person, his friend and biographer, John Forster.

Dickens was later sent back to school, but when his parents could again no longer afford to pay for their son’s education, he found work first in a law office, and then as a newspaper reporter, covering the proceedings of Parliament. He taught himself shorthand and soon was known as the fastest and most accurate parliamentary reporter in the City.

While working as a reporter, Dickens began writing semi-fictional sketches for magazines, eventually publishing them as Sketches of Boz. His next work was the Pickwick Papers, which was published in a relatively new serial format. Each month, as twelve-thousand word section of the book was sold in a “number,” at a shilling each. This made a long book affordable to many more people. After Pickwick, all of his subsequent books, until A Christmas Carol, were first sold in serial form.

Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol in six weeks, from October 1843 until the end of November. It was the first story Dickens wrote all at once, and the effect on Dickens’s writing is noted by one critic who writes, “It is a transitional work between the early novels and his mature work. This is the first occasion of Dickens discovering a plot sufficient to carry his message. [Dickens]… at last began to keep a steadier eye on the purpose and design of his work which was to characterize his work from Dombey and Son [the novel following Carol] onward.”

Dickens was in debt when he hoped to turn a quick profit from A Christmas Carol royalties. As one biographer described it, his bank manager had given his muse an enthusiastic push. A Christmas Carol was a best seller and Dickens expected his first royalty check to be £1,000, but due to the high production cost of the book–in part because of his many last minute changes and its expensive materials–he received only £250.

Dickens and Christmas

Charles Dickens was an outgoing, playful man who loved games and parties. The act of writing A Christmas Carol affected him profoundly. During its composition, he wrote a friend that he “wept and laughed, and wept again, and excited himself in the most extraordinary manner in the composition; and thinking whereof he walked about the black streets of London fifteen and twenty miles many a night when all the sober folks had gone to bed.”

Despite Dickens’s frequent criticism of organized religion and religious dogma, he loved celebrating Christmas. Of the Christmas following the publication of A Christmas Carol, Dickens wrote in a letter, “Such dinings, such dancings, such conjurings, such blind-man’s bluffings, such theatre-goings, such kissings-out of old years and kissings-in of new ones never took place in these parts before. To keep Chuzzlewit going, and to do this little book, the Carol, in the odd times between two parts of it, was, as you may suppose, pretty tight work. But when it was done I broke out like a madman, and if you could have seen me at a children’s party at Macready’s the other night going down a country dance with Mrs. M. you would have thought I was a country gentleman of independent property residing on a tip-top farm, with the wind blowing straight in my face every day.” Jane Welsh Carlyle (wife of Thomas) was a guest at his New Year’s Eve party that year and described the performance by Dickens and his best friend. “Dickens and Forster above all exerted themselves till the perspiration was pouring down and they seemed drunk with their efforts. Only think of that excellent Dickens playing the conjurer for one whole hour–the best conjurer I ever saw.”

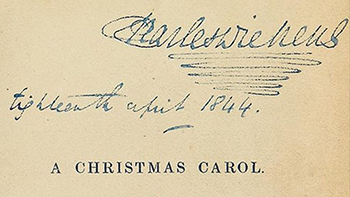

Dickens’s signature in a presentation copy of A Christmas Carol

On January 15, 1844, Charles and Catherine’s son Francis Jeffery was born. Dickens’s biographer Peter Ackroyd (1990) points out the irony that one month after the publication of A Christmas Carol, which glorifies the family and especially the pitiful Tiny Tim, Dickens’s feeling for his own youngest child were more Scroogish than Cratchity. Dickens wrote a friend, “Kate is all right again, and so they tell me is the Baby. But I decline, (on principle), to look at the latter object.” When the Dickens family left for Italy in July, they left the baby in England with his maternal grandmother.

After A Christmas Carol, Dickens wrote another “Christmas book,” The Chimes, for Christmas 1844. Dickens wrote three more Christmas books and many Christmas stories. He edited two magazines, Household Words, and All the Year Round, which published annual “Christmas numbers” for which he wrote and edited stories. Writing about Christmas and, later, giving readings from Carol were important sources of income for Dickens for the rest of his life.

A Christmas Piracy

When Dickens toured the U.S. in 1842, just a year before writing A Christmas Carol, he hoped to further the establishment of international copyright laws. His books had been reprinted in the U.S., and, although they sold thousands of copies, he had never received royalties. U.S. publishers believed that he, along with other British writers, were compensated for their work in their own country, and, if they saw their books published overseas, that popularity was payment enough. Dickens supported himself and a growing family solely through his writing and publishing efforts. His writing had ensured his rise from the lower-middle class, and theft of his work by enterprising foreigners left him feeling bitter and cheated. In the end, Dickens retaliated in writing the hilariously satirical memoir, American Notes, and the novel Martin Chuzzlewit. In both books Dickens portrays American in unflattering characterizations.

Overseas publishers were not the only competitors for Dickens’s genius. British copyright law was relatively new, and authorial rights were still unprotected. Dickens’s works were sold in unauthorized reprints and bald plagiarisms from the beginning of his career. In many of these publications only characters’ names were slightly changed, leaving the story, but not the inimitable language, reasonably intact. Pirates also presented widely popular theatrical performances. Dickens attended on of these performances of the Carol and found it “heartbreaking.”

Dickens sued publishers who pirated the Carol. The courts decided in his favor, after which he exclaimed in a letter, “The pirates are beaten flat. They are bruised, bloody, battered, smashed, squelched, and utterly undone.” But the publishers who pirated his works declared themselves bankrupt, and the lawsuit grew so complicated Dickens had to pay £700 to disentangle himself from it. He later wrote bitterly of his experience, “It is better to suffer a great wrong than to have recourse to the much greater wrong of the law.”